|

|||||

| THE TAKING OF VERSAILLES | |||||

| “ Landmark Fashion Show Broke Racial Barriers, Showcased U.S. Designers.”

|

|||||

| A fund raiser for the restoration of the legendary palace (an unhappy home, if ever there was one, for some long- ago crowned heads) the 1973 “Battle of Versailles” was a publicity stunt conjured up by the late, great publicist, Eleanor Lambert; a fashion guerre à mort between five French couturiers – Yves St. Laurent, Christian Dior (with designer Marc Bohan at the design helm), Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Cardin and Emanuel Ungaro – and five American upstarts. In the catwalk-crosshairs with yankee whippersnappers Oscar de la Renta, Bill Blass, Anne Klein, Halston and Stephen Burrows , the French contingent was the odds on favorite to win.

But, as so often happens, fate had a far different outcome in mind. As eight black models – Pat, Alva, Norma Jean, Bethann and Billie among them – sashayed, strutted and “pizzazzed” into action, the audience came to its feet, clapped, roared and flung their proverbial hats in the air and nothing – not America, not fashion, not the perception of beauty – was ever the same. |

|||||

|

|

||||

| Distinguished, among the ranks of many gifted and internationally recognized African American fashion designers, is Patrick Kelly who, in 1988, was the first American – and the first person of color – to be admitted as a member to the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter et des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode. Ann Lowe, memorialized by the five Ann Lowe creations housed in the permanent collections of the Met’s Costume Institute, was tapped by Jacqueline Bouvier to design the wedding gown she’d wear at her marriage to John F. Kennedy. And, while the list goes on to include, among others, Willi Smith, Tracy Reese and Coty Award winner, Jeffrey Banks, for our purposes it’s all about Stephen Burrows.

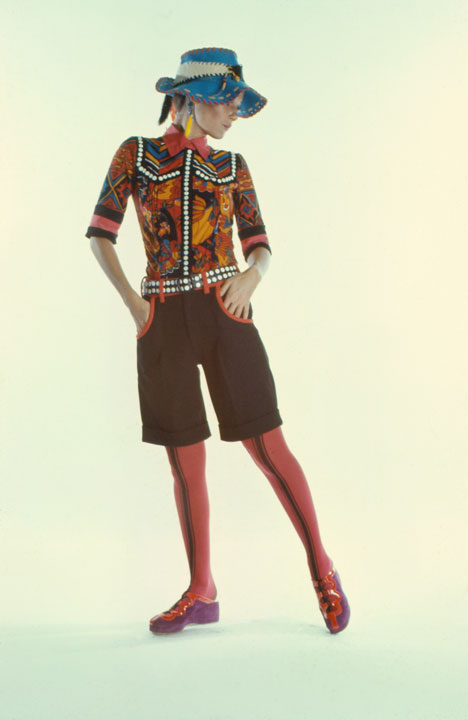

From the outset in 1966, Stephen’s clothes for the “O” Boutique (across from the long-shuttered Max’s Kansas City) – in all their studded, fringed, second-skin sensuality – started a virtual cult; uniforms of choice for the wild child habituées of ‘studio’ in the heady, steamy, sex-and-whatever infused days of that era. Championed by the very astute Geraldine Stutz, Stephen Burrows’ World at Henri Bendel brought a cool, hip East Village sensibility to 57th Street where the likes of Cher, Diana Ross, Liza Minnelli and Lauren Bacall, among scads of other A-listers, pounced on the vividly color-blocked, “lettuce-edged” Jasco matte jerseys that slipped over the body like a slinky down a staircase.

Referred to by The New York Times as an “American Original,” legendary, iconic and three time Coty Award winner, Burrows was honored, in 2006, on the occasion of his fortieth anniversary as a designer, with the CFDA’s Board of Directors Special Tribute Award. His career has been the subject of a number of retrospectives, most recently an exhibit, When Fashion Danced, mounted at the Museum of the City of New York, in March 2013. |

|

||||

|

And here’s the thing: A private tour of that exhibit accompanied by – wait for it – Stephen Burrows himself, was arranged for the Fashion Group International 2013 Regional Directors Conference.

Stephen Burrows is the first African American designer to achieve international recognition and acclaim, and the well—deserved and much applauded reputation as the guy who planted a “black eye” squarely on the face of the French designers at-the-ramparts at “The Battle of Versailles. “As C.Z Guest commented, “not since Eisenhower have the Americans had such a triumph in France.” |

|||||